There is a good chance that the verse cited in the above title, a verse from Psalm 68, is a favorite Biblical verse with members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. There is somewhat less of a chance that many people in North America today know much about this ancient Orthodox community.

The Gospel came early to Ethiopia. The first one to bring the Good News of Jesus there was the Ethiopian eunuch, mentioned in Acts 8:27, who was baptized by the deacon Philip before returning to his native land and the service of Candace, the queen of the Ethiopians.

A more formal and structured mission came to Ethiopia in the fourth century through the work of St. Frumentius. When he was a boy, Frumentius and his brother were shipwrecked on the Eritrean coast. They worked at the royal court and rose in the service of the king, eventually converting him to the Christian Faith and to baptism. The king sent Frumentius to the patriarch in Alexandria to ask him to supply a bishop for his country to help him bring them to Christ. The patriarch ordained Frumentius as a bishop and sent him back. Frumentius became popularly known as Abuna Selama, “Father of peace.” Through his work, the Ethiopian Axumite kingdom was one of the first kingdoms to embrace Christianity as its official religion.

What a story: really, you can’t make this stuff up. Since that time the Ethiopian Church has been administratively part of the Coptic Church of Alexandria, receiving its administrative independence from it only in 1959. It is sometimes known as the Ethiopian Tewahedo Church. The word “tewahedo” is a Ge’ez word meaning “unified” or “one,” and it refers to their belief that Christ has only one single unified divine-human nature, rather than two natures, divine and human, as the Council of Chalcedon proclaimed in 451. Thus, one possible translation of “tewahedo” might be “monophysite.”

The whole ecumenical question of dialogue with the monophysite churches (they prefer the term “non-Chalcedonian” or “oriental churches”) is a complex one. Some scholars involved in the official Chalcedonian/ non-Chalcedonian dialogue have concluded that the Christological difference is merely one of terminology. Either way, the non-Chalcedonian churches confess with us that Christ is 100% human as well as being 100% divine. They consider themselves to be fully Orthodox, whatever difficulties may be now encountered along the ecumenical way.

Relations with the Ethiopian Orthodox illustrate the complexities of ecumenical relationships in general. Everyone is attached in some way to everyone else, and we are all part of a number of different and over-lapping families. For example, we are all part of the human family, regardless of our religion (or lack of it). And all Orthodox, Roman Catholics, or Protestants are part of the Christian family. The question may be asked, is the Ethiopian Tawahedo Church part of the Orthodox family, or has it been severed from that family by schism, given that they do not confess with us the proclamation of the Council of Chalcedon, considered by us to be the Fourth Ecumenical Council?

The question of schism is not as simple and easy to answer as it might first appear, and cannot be fully resolved simply by asking whether or not any two churches are in official communion and can share each other’s Eucharists. (The answer in the case of Orthodoxy and the Tawahedo Church, by the way, is “No, they cannot yet do so.”) For consider other schisms in church history, some within recent memory. There was a time not so long ago that the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR for short) was out of Eucharistic communion with the most of the Orthodox world, including Constantinople and Moscow, but few would suggest that during that time it was not authentically Orthodox. Like I said, the question of schism has a slippery way of evading easy answers.

While we wait for full and final resolution of such ecumenical questions, a good way forward for the vast majority of us Orthodox who are not bishops is to treat our Ethiopian Orthodox neighbours with love. This involves getting to know them, and letting them get to know us, visiting their churches and inviting them to visit ours. It involves inviting them to our get-togethers and food festivals and attending Bible studies together. It is through these exchanges and loving relationships that the truth will finally emerge. It is up to the bishops to sort out difficult canonical questions. It is up to all of us, while we patiently wait for these episcopal results, to walk with our Christian neighbours in love—including our neighbours from the Ethiopian Tawahedo Church.

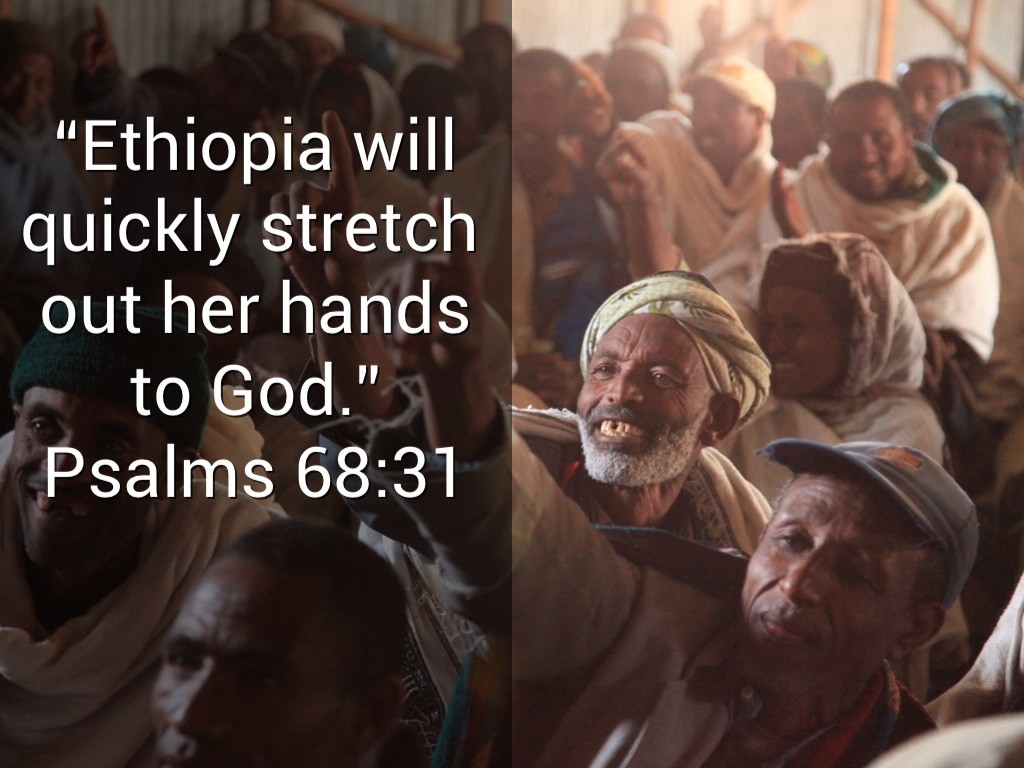

Photo: File: Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Paintings, Yeha, Ethiopia. From Wikimedia Commons