C. NDUTA

MG Africa

Ge’ez is the only original African script taught and used widely in everyday interaction – in Ethiopia and Eritrea. It is also the most successful.

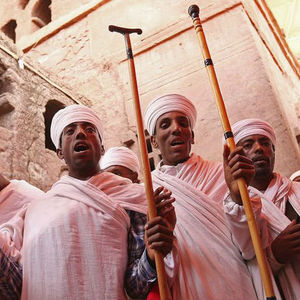

Followers of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The native African script of Ge’ez is itself extinct, used only on the liturgy of Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox churches. (AFP)

Followers of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The native African script of Ge’ez is itself extinct, used only on the liturgy of Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox churches. (AFP)

Last weekend, a Kenyan made the news by announcing he had developed an indigenous script for the Luo language. In no time, #WritingLuo was the top trending topic in Kenya on Twitter.

The developer, Kefa Ombewa, said he was out to “de-Latinise” the Luo language, arguing that African languages needed indigenous symbols to express their nuances that the Roman alphabet simply cannot capture.

Reception on social media so far has largely treated the development of the script as just another flamboyant curiosity, but could Ombewa be on to something?

The desire to express African languages in locally developed symbols has been strong through the decades. Written language embodies historical identity and cultural power—thus when Israel became a state in 1948, it revived the Hebrew language from near-oblivion, not just as a tool of unifying modern Jews, but also as a political symbol of their claim of a connection to ancient Israel.

Today, most African languages are written in the Latin or Arabic alphabets.

However, Latin and Arabic themselves developed from ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. Despite the modern diversity of writing systems, historians believe that ancient writing developed independently in only four places—Egypt, Iran/Iraq, China, and Mesoamerica (the cultural area in the Americas, extending approximately from central Mexico to Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica).

Ge’ez in the mix

All other scripts are derivatives or influences of these four: For example, Arabic is derived from ancient writing in Iran/Iraq; Japanese and Korean and derived from Chinese, and Latin alphabet is derived from ancient Greek, which adopted its alphabet from Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Thus it could be argued that European languages today are written in script derived from Africa—not the other way around.

Although Africa is known for its oral traditions, there have also been several indigenous African writing systems, some of which are still in use today.

Used in Ethiopia and Eritrea, Ge’ez is the only native African script taught in school today used widely in everyday interactions. Dating back to the 9th century BC, Ge’ez itself is an extinct language, much like Latin, only used in the liturgy of the Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox churches.

But the Ge’ez script is used to write Amharic, Tigrinya, Tigre and most other languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea. And with a population of over 90 million residing in those two countries, Ge’ez is the most successful native African script today.

Ge’ez probably developed over the course of several centuries. But another native African script, Vai in Liberia and Sierra Leone, is credited to one man, who invented the Vai writing system in the 1830s, a Liberian named Momolu Duwalu Bukele.

It is said the script was revealed to him in a dream, though it is more likely that the Cherokee syllabary in North America provided a model for the design of Vai writing. At the time, many Cherokee had migrated to Liberia in the early 1830s, just at the time when Cherokee itself was developing its written script.

Cameroon’s Bamum

Another script developed in modern times is the Bamum script, invented by King Ibrahim Njoya, the 17th king of the Bamum of West Cameroon in 1896. The script, also named A-ka-u-ku after its first four letters, is rarely used today, but a fair amount of material written in this script still exists.

But King Njoya’s grandson and current sultan of Bamum, Ibrahim Mbombo Njoya, has since transformed his palace into a school to re-teach the Bamum script, initiating The Bamum Scripts and Archives Project in 2005 to bring it back from the brink of extinction.

Further south in Malawi is the Mwangwego alphabet developed in 1977 for Malawian languages by Nolence Mwangwego. But it is not used widely in everyday interactions. Other African scripts, such as Nubian and Meroitic, have fallen into disuse and are considered extinct.

But most African languages today, particularly south of the Sahara, are written using the Latin alphabet. This presents many difficulties in expressing some sounds that are not found in European languages.

In the 1960s and 1970s, UNESCO hosted several “expert meetings” on the subject, including a seminal meeting in Bamako in 1966, and one in Niamey in 1978, where a standard African alphabet—using Latin letters but incorporating many other non-Latin sounds—was proposed. But it is yet to be widely adopted.